VVP: Art 434 & Engl. 410

- Dan Callis and Chris Davidson

- Website for Vision Voice and Practice: An Interdisciplinary Course in Art and Creative Writing

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

The Worth of the Work

A nice example of the kind of work Sayers champions can be examined in this article. My favorite line:

These Brooklynites, most in their 20s and 30s, are hand-making pickles, cheeses and chocolates the way others form bands and artists’ collectives.

It takes work to make this kind of thing happen. And patience. And interest in the thing itself. I'm reminded of Sayers' description of the shareholders of the brewery who don't just want to know about the bottom line but who "want to know what goes into the beer." Such principles of work and patience apply to visual artists and writers, of course, but artists and writers always want to make a mark, to achieve for their work some permanence. What about those who, like these Brooklynites, make something one consumes (in the truest sense) and which, by that consumption, vanishes from the world? There's something lovely in the idea, because it means finding validation in things other than in what is tangible and measurable: community, sustainability, stewardship, the pleasure of process, the worth of the hand-made thing. A show like How It's Made finds its audience in showing us the way what's lying around the house is manufactured. As one writer has pointed out (in an article I can't find), part of the show's mesmerizing appeal is its lack of a human presence. Our stuff - including much of our food - is made mostly by robots on assembly lines. I don't want to paint too broad and unfair a picture, but you don't hear a robot remark about the Fritos it has roasted and bagged, "These are pleasant to the sight and good for food..." Which may be a long way of explaining the appeal Richard Scarry's books have for my children (and me!).

Monday, February 23, 2009

Presentations

Our first group poet/arist presentations looked at the work of Joseph Cornell and Marianne Moore. The presentations focused on the voice and vision of Moore and Cornell's practice.

Confusion of Categories

One of the things Dorothy Sayers' writes in her essay "Why Work?", written during WWII in a period of scarcity and rationing, a crisis not totally unlike the economic crisis we currently face:

We have had to learn the bitter lesson that in all the world there are only two sources of real wealth: the fruit of the earth and the labor of men; and to estimate work not by the money it brings to the producer, but by the worth of the thing that is made.The best way to understand "the thing that is made," according to Sayers, is to "serve it." She writes,

[The worker's] satisfaction comes, in the god-like manner, from looking upon what he has made and finding it very good. He is no longer bargaining with his work, but serving it. It is only when work has to be looked on as a means to gain that it becomes hateful; for then, instead of a friend, it becomes an enemy from whom tolls and contributions have to be extracted. What most of us demand from society is that we should always get out of it a little more than the value of the labor we give to it. By this process, we persuade ourselves that society is always in our debt - a coviction that not only piles up actual financial burdens, but leaves us with a grudge against society.Further, Sayers writes,

The greatest insult which a commercial age has offered to the worker has been to rob him of all interest in the end product of the work and to force him to dedicate his life to making badly things which were not worth making.Finally, describing how the damage a confusion of categories wreaks on society - in this case, a confusion of the right role of work in a person's life - is not mitigated by good - or even "holy" - intentions, Sayers comments,

No piety in the worker will compensate for work that is not true to itself; for any work that is untrue to its own technique is a living lie. [Emphasis mine.]This applies to the artist's and writer's work, but also to the furniture maker's, the gardener's, the grocer's, the engineer's and the rest. But it seems especially relevant to this class, where we flirt with the idea of blurring categories. We tread carefully, therefore. A short and entertaining essay, entitled "Great Book, Bad Movie," which explores what happens when you don't tread carefully, can be read here.

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Miscellany

A lot has happened in the past week that has gone undocumented here. Our discussion of Dorothy Sayers' essay "Why Work?" has stayed with me, as has the idea, described a couple posts down, that progress brings tradeoffs. Two columns that address this, one of which is about the movie Wall-E, can be found here and here.

Sayers' essay also prompted my searching of Genesis, some passages of which I shared in class:

More:

Finally:

Sayers' essay also prompted my searching of Genesis, some passages of which I shared in class:

And God saw that is was good. - 1:12bThis is the first time this phrase is used in the creation story. One of the OED entries defines 'good' as "Having in adequate degree those properties which a thing of the kind ought to have," a definition anyone who makes should understand.

More:

And the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed. Out of the ground the LORD God made to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food... - 2:8-9Here, aesthetic consideration ("pleasant to the sight") is fused with utility ("good for food").

Finally:

The LORD God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it. - 2:15Before the fall, the man was put to work. He was made to work. Describing Adam & Eve's Edenic labor, Milton has it thusly:

On to their morning's rural work they hasteAnd, last, at the risk of making this post 'overwoody,' a word about 'moral,' as used in Eagleton's definition of poetry, which we discussed yesterday:

Among sweet dews and flow'rs; where any row

Of fruit-trees overwoody reached too far

Their pampered boughs, and needed hands to check

Fruitless embraces... v: 211-15

A poem is a fictional, verbally inventive moral statement in which it is the author, rather than the printer or word processor, who decides where the lines should end. 25The OED, again, on "moral" (first definition):

Of or relating to human character or behaviour considered as good or bad; of or relating to the distinction between right and wrong, or good and evil, in relation to the actions, desires, or character of responsible human beings; ethical.This seems to comport with Eagleton's elucidation of the term:

...morality in its traditional sense...is the study of how to live most fully and enjoyably; and the word 'moral' in the present context refers to a qualitative or evaluative view of human conduct and experience. 28This means that poems that don't appear to have a readily discernible moral dimension do, in fact, even poems as (merely) observational as haiku, like this one by Matsuo Bashō:

By the old temple,

peach blossoms,

a man hulling rice.

Friday, February 13, 2009

Ways of Seeing

Francis Alys:Fabiola

Francis Alys:FabiolaOne of the required class texts is John Berger's, Ways of Seeing. In discussing the first chapter we spent a good deal of time talking about issues of reproduction, originality and place. A work of art, the physical object, is created with the intention of physicality. The surface of the work is imprinted with the presence of the artist's actions. It's generally assumed that this surface will be received (seen) by an individual viewer in a specific location offering what Daniel Siedell refers to as "a unique and complex "hypostatic union" between sensuous material and rational ideas." While reproduction and the technology of distribution provide a democracy of accessibility one does have to seriously consider what is lost in the vision and voice of the work when it is delivered/received via web or powerpoint.

A few days after the class discussion I stumbled into an amazing exhibition at LACMA. Francis Alys: Fabiola, a collection of nearly three hundred objects, all original works, all copies of a single work. The subject matter is a fourth century Christian saint known as Fabiola. The prototype from which every work derives is a lost painting by a late-nineteenth century French academician named Jean-Jacques Henner. Original, reproduction, original.

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Learning and Losing

The discussion about Dorothy Sayers' remarkable "Why Work?" today was fantastic, but I fear her essay can make us (or me) feel despair, given how far things have progressed away, in the last sixty or so years, from her vision of work and society. This afternoon, I was reminded of the following passage from Eagleton, Chapter 1, which speaks to the concerns we have about technological progress and its consequences:

If modern technology can be oppressive, it can also be emancipatory. If it can dilute experiences, it can also increase their accessibility. Even the Giant's Causeway Experience can help to educate us, in however formulaic a fashion. History-as-heritage is arguably preferable to no history at all. Such cultural technology opens up a world of possibility unimaginable to our ancestors. Only a dialectical viewpoint, one which weighs the gains of modernity along with its losses, can do justice to it. And this is inimical alike to the cultural Jeremiahs, for whom civilisation has been going downhill ever since the invention of the wheel, and the wide-eyed cultural progressivists, for whom R.E.M. has thankfully put paid to Rembrandt.Can such a (more hopeful) view of modern life fit with Sayers' argument? [UPDATE: In the current issue of the New Yorker, an article about Florida reads as a demonstration of the kind of judgment Sayers describes. A companion video to the article can be viewed here.]

Avant-garde artists like the Futurists and Surrealists plucked new kinds of art from the very speed, flatness, flux, randomness, irregularity, fragmentation and multiplicity of modern experience. A whole new poetics seemed possible. The most celebrated poem of the twentieth centure, T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land, registers this haemorrhaging of experience from modern urban life, but views it as a spiritual catastrophe. Poets like Mayakovsky, Brecht and Breton, by contrast, did not look upon the emptying of the human subject with horror. Maybe being scooped out and dismantled might prove a prelude to being put together again, this time more productively. To learn something, as George Bernard Shaw remarked, always feels at first like losing something. 20-21.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Second Post

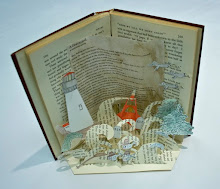

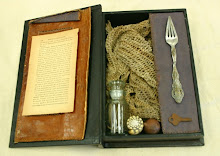

Our first class field trip involved visiting two museums. The first was the Hammer Museum to see "Oranges and Sardines, conversation on Abstract Painting". The title is in reference to Frank O'Hara's "Why I am not a Painter". The second exhibition we visited was at MOCA Pacific Design Center. "To Illustrate and Multiply: an Open Book" This was an extensive survey show of artist books.

View the Marianne Moore slideshow by clicking here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)