Neat: Link. We could have submitted some stuff!

Also, there's this angry, fun-to-read, and challenging rant about poetry-makers, like some of us: http://strongverse.blogspot.com/2008/03/what-holds-us-back.html

Finally, are you a hipster? Do you have hipsterish tendencies? Be careful! Not all will appreciate you.

VVP: Art 434 & Engl. 410

- Dan Callis and Chris Davidson

- Website for Vision Voice and Practice: An Interdisciplinary Course in Art and Creative Writing

Monday, June 1, 2009

Friday, May 22, 2009

But these things are...

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

Collaboration!

We've had some fun this semester collaborating, as the images on the right side of this page attest. Erin sent me a link to this utterly enjoyable web project, which shares a spirit of fun that recalled to me the Flaming Lips' parking lot experiments from the late '90s. The hope projects like these carry in them!

Monday, May 11, 2009

student work

rooms with no windows

couples old and young alike and even the single will glide through

model homes and other reselling dwellings and whisper

about the quality of the view. oh, that the fate of a real estate agent

lies just outside double-panes and other shuttered frames.

what hope for his career without lakeside or skyline?

as the mole thrives underground while the eagle

perches high on mountain pine,

the nearsighted and blind are the real estate agent's Godsent blessings,

the only hearts in which unlovely lots find admiring spots.

- Melissa Gutierrez

couples old and young alike and even the single will glide through

model homes and other reselling dwellings and whisper

about the quality of the view. oh, that the fate of a real estate agent

lies just outside double-panes and other shuttered frames.

what hope for his career without lakeside or skyline?

as the mole thrives underground while the eagle

perches high on mountain pine,

the nearsighted and blind are the real estate agent's Godsent blessings,

the only hearts in which unlovely lots find admiring spots.

- Melissa Gutierrez

Saturday, May 2, 2009

Poetry Games

Last week we made, as an on-the-spot collaboration, versions of renga. Haiku derived from this form of collaborative poetry, which, in a drastically reductive definition, goes likes this: Person A makes a three-line, haiku-like poem. Person B "completes" the poem with a two-line envoy. Person C uses that envoy as the first two lines of a new poem, which she completes by writing another haiku-like poem. And so on. Part of the fun is how the poems keep transforming, and could, endlessly, as long as the energy of the participants holds up. The class was broken into three groups, and here is the result of one group's play:

I ripped the fringe

off of the red silk tablecloth

the plates fell

and the ringmaster's elephant

gave a big trumpet

~

And the ringmaster's elephant

gave a big trumpet

like a saxophone man,

the triangular brass post

shines for pennies

~

Like a saxophone man,

the triangular brass post

shines for pennies

round and round,

falling into the looking pool

~

Round and round,

falling into the looking pool

I grab the neck

of a black swan

who shrinks and sinks

~

I grab the neck

of a black swan

who shrinks and sinks

into dusky night

to sleep, to rest

~

Into dusky night

to sleep, to rest

her hair smelled of vodka and weed

her dress ripped in three places

her mind clouded

[The implied violence in this example was not unusal. Each of the group's poems had something--a cougar grabbing a zoo spectator; a kid getting hit--like this, indicating, perhaps unconsciously, the stress of the end of the semester. Better in a poem than on the streets.]

I ripped the fringe

off of the red silk tablecloth

the plates fell

and the ringmaster's elephant

gave a big trumpet

~

And the ringmaster's elephant

gave a big trumpet

like a saxophone man,

the triangular brass post

shines for pennies

~

Like a saxophone man,

the triangular brass post

shines for pennies

round and round,

falling into the looking pool

~

Round and round,

falling into the looking pool

I grab the neck

of a black swan

who shrinks and sinks

~

I grab the neck

of a black swan

who shrinks and sinks

into dusky night

to sleep, to rest

~

Into dusky night

to sleep, to rest

her hair smelled of vodka and weed

her dress ripped in three places

her mind clouded

[The implied violence in this example was not unusal. Each of the group's poems had something--a cougar grabbing a zoo spectator; a kid getting hit--like this, indicating, perhaps unconsciously, the stress of the end of the semester. Better in a poem than on the streets.]

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Practice, Craft

Here's an article discussing, essentially, the third part of our course, practice, that activity we use to hone our craft. Let's hear it for those who labor!

Thursday, April 23, 2009

The Pleasure of Close Reading

Chapter 5 of Eagleton's How to Read a Poem closely examines a series of verse excerpts in order to define and demonstrate concepts like the texture of a poem, its tone and pitch, and its ambiguous nature. In a recent column in Slate, Robert Pinsky does the same thing with poems by Edward Thomas and Gerard Manley Hopkins. You can read it here.

Saturday, April 11, 2009

Student Work

A Mind Full

Contemplation and consumption seem to

hit home in the nineteenth year of the

omnibus. With concentration I focused

on the morsels that I consumed

without hesitation. I avoided frustration

and I considered the completion of the omnibus

that had taken nineteen years to reach fruition.

Now, raw is the "tion" of my tongue invalidating

and abandoning the "ing" ending.

- Allison Castellano

~

Costco Can Turn You Into An Obsessive Bitter Overweight Spinster

Alice once told me that she had two vices:

men and Cheez-Its.

I didn't believe her until

she finished a three-pound Costco box

in two days after her boyfriend

left her for a girl on the subway

reading Hemingway.

I told her she deserved better.

She finished another box

and emptied her apartment.

- Shirly Tagayuna

~

Stuck

An empty page stares

Back at me as I labor to get the inside out

My pen held in a cracked hand

Replete with dusty white rivers

Because the air is dry and

Words feel dry.

Much to say but how to convey

A life of hard lessons

The depth of questions

And joy in the day to day?

- Michelle Kohout

~

Morning

traps itself. Sunlight and fog,

dream and arpeggio waking-thought, before

movement, before time are things to be sought.

- Matt Gundlach

Contemplation and consumption seem to

hit home in the nineteenth year of the

omnibus. With concentration I focused

on the morsels that I consumed

without hesitation. I avoided frustration

and I considered the completion of the omnibus

that had taken nineteen years to reach fruition.

Now, raw is the "tion" of my tongue invalidating

and abandoning the "ing" ending.

- Allison Castellano

~

Costco Can Turn You Into An Obsessive Bitter Overweight Spinster

Alice once told me that she had two vices:

men and Cheez-Its.

I didn't believe her until

she finished a three-pound Costco box

in two days after her boyfriend

left her for a girl on the subway

reading Hemingway.

I told her she deserved better.

She finished another box

and emptied her apartment.

- Shirly Tagayuna

~

Stuck

An empty page stares

Back at me as I labor to get the inside out

My pen held in a cracked hand

Replete with dusty white rivers

Because the air is dry and

Words feel dry.

Much to say but how to convey

A life of hard lessons

The depth of questions

And joy in the day to day?

- Michelle Kohout

~

Morning

traps itself. Sunlight and fog,

dream and arpeggio waking-thought, before

movement, before time are things to be sought.

- Matt Gundlach

Friday, April 10, 2009

Losing Your Bearings

This past Tuesday, for his contribution to the song-of-the-day part of the class, Kevin showed us the video for the Alphabeat song "Fascination." Why? Because, he said, he liked the song. Good enough for me. The song contained all one can hope for in pop music: it was catchy, light, joyous beyond what the material would seem to warrant. This is what makes songs like this so much fun.

After Kevin played us the video, I played a couple of songs by the Beach Boys that were recorded during the rise and collapse of the SMiLE album. You can read the story here. In the first, unfinished version of "Wind Chimes" that we listened to, we could hear some of composer Brian Wilson's optimism, which came from enjoying an already successful career, a record company backing him after a hugely popular (and pretty strange, if you think about it) single, a rock press repeatedly proclaiming his genius, and a band waiting for its next recordings to inspire an even greater wave of fan adoration. This earlier version of "Wind Chimes," like "Good Vibrations," embodies a proto-hippie utopianism: The wind chimes and the wind and me, man, we're all part of the cosmic order. Heavy.

So when, after recording delays and interpersonal squabbling and record company hostility and nascent fan desertion and the press revoking its endorsement, and after one more Brian Wilson psychic collapse, the Beach Boys re-made "Wind Chimes," in this version, which we also listened to in class, the sound has changed: We now hear a person--and group of people--losing their bearings. It is for me the more interesting of the two recordings. There's more going on musically (listen to the amazing acapella ending!) and thematically: the song predicts and evokes the sinister underside of all that hippie utopianism, creepily expressed later in the decade in the movie Gimme Shelter. By losing his way, Brian Wilson temporarily gained a vision.

We'll read later in the semester Flannery O'Connor's persuasive claim that only by keeping your bearings can you truly see. And maybe this is the truer case for Brian Wilson, as well. Music, and not the stuff that came with it, was what rooted him. He had been singing with his brothers (future bandmates) and sister since they were children, with Mom and Dad at the piano, working out the harmonies of hymns and standards. After his world fell apart, he could still sing with his brothers (and cousin, also in the band). That's what makes this song more substantially hopeful than the earlier version: It charts in its trajectory a means of respite. After the unsettling harmonies and insistent organ and sound effects drop away, what's left is the sound of voices working, harmonically, together. For Wilson, after the darkness, he still could make something, and make it well, and within a community who loved making this thing with him.

Wednesday, April 8, 2009

Two Poems

Last night, Heather McHugh gave a reading (with August Kleinzahler) at LACMA, and it was about as scenic a venue as you could hope for. The poets were framed by a huge black painting (or what I took to be a painting) and were flanked by Richard Serra's immense sculptures Sequence and Band. McHugh's introductions were like little lessons in perception, and two poems in particular stood out: "Etymological Dirge" and "With wine and being lost, with," a Paul Celan poem translated by McHugh and Nikolai Popov. I couldn't find this one online, but it's worth seeking out. You can read another of their Celan translations here.

The idea for the reading was inspired: Speaking the well-considered word into a visual Eden. But the acoustics were terrible. The sofest shuffling of feet reverberated throughout the place and seemed to gain volume and momentum, like a roll of thunder. Kleinzahler's habits of delivery made hearing his work particularly difficult, and McHugh's was transmitted more effectively via her positioning of the mic (she stood away from it) and her mild projection, but I still missed a fair amount of what she said. In other words, when putting together future readings, the LACMA people and co-organizer USC might might look for another room on that indulgent, resplendent campus. Gregorian chanters, on the other hand, should be booked immediately.

The idea for the reading was inspired: Speaking the well-considered word into a visual Eden. But the acoustics were terrible. The sofest shuffling of feet reverberated throughout the place and seemed to gain volume and momentum, like a roll of thunder. Kleinzahler's habits of delivery made hearing his work particularly difficult, and McHugh's was transmitted more effectively via her positioning of the mic (she stood away from it) and her mild projection, but I still missed a fair amount of what she said. In other words, when putting together future readings, the LACMA people and co-organizer USC might might look for another room on that indulgent, resplendent campus. Gregorian chanters, on the other hand, should be booked immediately.

Monday, April 6, 2009

Art, Reading, Memory

Last week's issue of the New Yorker contained a wonderful review of a show in New York featuring five paintings from Southern California's Norton Simon Museum. (In the words of the writer, Peter Schjeldahl: "inch for inch, the finest collection of European paintings west of the Mississippi.") Only an abstract of the article is available online, which is too bad, given the number of insightful and provocative claims Schjeldahl makes, many in the first paragraph:

When I came back to the poem last week, I felt something similar to what Schjeldahl describes, that the work was flatter than I remember, perhaps literally so: seeing it on the page seemed to rob some of its magic. But reading it aloud a couple times, navigating my voice across its sentences and lines, I felt rising in me something Schjeldahl also describes: "This time I get it!" (You can listen to Hass read the poem here. Scroll down to February 21, 2008. The poem is roughly at the 28-minute mark.)

This has been a recurring experience of mine, where my memory seems to threaten to undo--or actually undoes--whatever at-the-time valuable experience my reading seems to be leading me through. Close the book, and what remains for me is a feeling, perhaps vaguely outlined, but the details, or some of the best sentences, remain locked away until time and opportunity affords me a chance to open its pages again. This may be a product of unsystematic reading, or a weakness of memory, or of simply being human. Contextualization may help. The final paragraph of Schjeldahl's essay, like the first, offers a remarkable series of insights into the way paintings (or texts?) are arranged within a collection. The Frick's collection, in New York City, Schjeldahl characterizes by its "relative quietude, propriety, and subtlety," expressed mostly in portraiture and landscape. (He uses these words to describe the originator of the collection, Henry Clay Frick, whose sensibilities mark the paintings found there.) The Norton Simon paintings, on the other hand, are brasher, more emotional and sensual. Schjeldahl says that these paintings "are not made altogether welcome [in the New York museum]. I fancied an irritable shudder in the Frick's sensitively indefinite Chardin, 'Still Life with Plums' (c. 1730), at the blazing Zurbarán's sudden proximity." The paintings themselves talk to--or at least turn up their noses at--each other! Listening to conversations like this may help us remember what we've forgotton.

[Awkwardly pious aside: The problem of memory is not limited to reading literature or looking at paintings. Seeing the news this morning, on the heels of weeks of troubling events, both financial and violent--sometimes both--one can't help feeling there's simply too much to remember, too much or too many to feel responsibility for. (I'm thinking here of Alyosha's notion--from The Brothers Karamasov--of responsibility.) What to do when faced with such overwhelming information, including the usual, recurring crises closer to home? I may write things I take to be poetry, but I can only hope that my inarticulate human speech is translated into something beyond utterance.]

We know what a great painting looks like while we are looking at one. Turning away, we don't exactly forget, but our recall of the experience--how we felt, looking--starts to edit what we saw. Some details and qualities are magnified; others evanesce. With time, the picture becomes more ours and less the painter's. My several visits to the best painting in the world, Velázquez's "Las Meninas" (1656), at the Prado, instruct me in the phenomenon. My first reaction is always disappointment at the coarse, almost drab, handmadeness of the big (but smaller than I thought) canvas, the absence of a glamour that I have cherished in memory and may have refreshed by contemplating glossy reproductions. (Reproductions are pandering ghosts; they tell us what we like to believe.) Then, rather abruptly, I find myself under Velázquez's spell again, as if I had never been before--pitying the fool that I must have been when I last viewed the work. This time I get it! But will I keep it? Not a chance.And the paragraph continues. (I love that bit about reproductions as "pandering ghosts.") Later, Schjeldahl curses his "memory's fecklessness" when describing a painting he loves by Francisco de Zurbarán, “Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose” (1633). This article came to me at an interesting time, as I've been reading--partly for pleasure, partly for a paper I'm to present at a conference next week--Robert Hass's book Time and Materials. I had heard Hass read some of the work in this book five years ago in Lake Tahoe, including a powerful poem called "The World as Will and Representation," a title taken from the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. After I heard him read it, I said to the people I was with, who also wrote poetry, "Who are we kidding? We're not poets!" What stuck with me was the poem's final image, of an alcoholic mother drinking and gagging, and of an ending address to the audience (that seemed very wise but in my memory lost all definition) that this image occassioned. Mostly what I kept was a feeling that I had experienced something beautiful and emotionally true.

When I came back to the poem last week, I felt something similar to what Schjeldahl describes, that the work was flatter than I remember, perhaps literally so: seeing it on the page seemed to rob some of its magic. But reading it aloud a couple times, navigating my voice across its sentences and lines, I felt rising in me something Schjeldahl also describes: "This time I get it!" (You can listen to Hass read the poem here. Scroll down to February 21, 2008. The poem is roughly at the 28-minute mark.)

This has been a recurring experience of mine, where my memory seems to threaten to undo--or actually undoes--whatever at-the-time valuable experience my reading seems to be leading me through. Close the book, and what remains for me is a feeling, perhaps vaguely outlined, but the details, or some of the best sentences, remain locked away until time and opportunity affords me a chance to open its pages again. This may be a product of unsystematic reading, or a weakness of memory, or of simply being human. Contextualization may help. The final paragraph of Schjeldahl's essay, like the first, offers a remarkable series of insights into the way paintings (or texts?) are arranged within a collection. The Frick's collection, in New York City, Schjeldahl characterizes by its "relative quietude, propriety, and subtlety," expressed mostly in portraiture and landscape. (He uses these words to describe the originator of the collection, Henry Clay Frick, whose sensibilities mark the paintings found there.) The Norton Simon paintings, on the other hand, are brasher, more emotional and sensual. Schjeldahl says that these paintings "are not made altogether welcome [in the New York museum]. I fancied an irritable shudder in the Frick's sensitively indefinite Chardin, 'Still Life with Plums' (c. 1730), at the blazing Zurbarán's sudden proximity." The paintings themselves talk to--or at least turn up their noses at--each other! Listening to conversations like this may help us remember what we've forgotton.

[Awkwardly pious aside: The problem of memory is not limited to reading literature or looking at paintings. Seeing the news this morning, on the heels of weeks of troubling events, both financial and violent--sometimes both--one can't help feeling there's simply too much to remember, too much or too many to feel responsibility for. (I'm thinking here of Alyosha's notion--from The Brothers Karamasov--of responsibility.) What to do when faced with such overwhelming information, including the usual, recurring crises closer to home? I may write things I take to be poetry, but I can only hope that my inarticulate human speech is translated into something beyond utterance.]

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

Under the Influence of Moore

Like Erin's poem, below, here's another poem (written by Jolene Nolte) that works within a Marianne Moore-like syllabic scheme:

City Cats

Somewhere between the Spanish steps and the farm-

er’s market, ancient ruins sit sunken

beside the modern city’s streets. Orange plastic wrapped around

posts keep people out, but stray cats

pay them no heed. What’s the Roman

Empire to them? Bare foundations,

truncated

columns serve as homes, thrones for these fortunate

cats. Seeing them, History gives a little laugh that her

most coveted empire’s re-

conquered, Caesar replaced by these

Roman cats.

City Cats

Somewhere between the Spanish steps and the farm-

er’s market, ancient ruins sit sunken

beside the modern city’s streets. Orange plastic wrapped around

posts keep people out, but stray cats

pay them no heed. What’s the Roman

Empire to them? Bare foundations,

truncated

columns serve as homes, thrones for these fortunate

cats. Seeing them, History gives a little laugh that her

most coveted empire’s re-

conquered, Caesar replaced by these

Roman cats.

Tuesday, March 31, 2009

Visitors

We've had the good fortune to have two excellent visiting poets the last couple-three weeks, Caley O'Dwyer and Cecilia Woloch. Both have worked at the intersection of art and poetry. Caley read to us from his series of poems responding to Mark Rothko's paintings, and Cecilia described for us a collaboration she participated in with an artist (whose name escapes me) for a show curated by Beth Shadur in Chicago.

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

The Wine Maker

bottle clank against wood,

my heart beats in unison-

as grapes press beneath the wheels

that carry my wife who carries

my child who squints at a

sliding sun overhead.

it is an indian summer this

october and the fermenting fields cry out,

erupting from the vine,

their sharp odor.

the conversations of chickens

flutter like old women gossips

who, over tea, pick apart the newest

plot of dirt.

i listen in.

it just might be a good year.

- Shirly Tagayuna

my heart beats in unison-

as grapes press beneath the wheels

that carry my wife who carries

my child who squints at a

sliding sun overhead.

it is an indian summer this

october and the fermenting fields cry out,

erupting from the vine,

their sharp odor.

the conversations of chickens

flutter like old women gossips

who, over tea, pick apart the newest

plot of dirt.

i listen in.

it just might be a good year.

- Shirly Tagayuna

Monday, March 23, 2009

Another Poem

Here's a poem by Ariel Okamoto, written in haiku stanzas (i.e. five syllables/seven/five):

The Poetry of Particle Physics

At the border of

Switzerland, CERN knows that the

possibility

of the Higgs boson

and the rumor of black holes

run through their giant

mass of particle

accelerator at speeds

approaching that of

light. Physicists grasp

after cosmological

constants and rethink

equations spitting

out answers with differences

of minute quanta.

Protons shoot on a

collision course, providing

a fireworks show

for those who know how

to interpret the soundless

echoes of strange quarks.

The Poetry of Particle Physics

At the border of

Switzerland, CERN knows that the

possibility

of the Higgs boson

and the rumor of black holes

run through their giant

mass of particle

accelerator at speeds

approaching that of

light. Physicists grasp

after cosmological

constants and rethink

equations spitting

out answers with differences

of minute quanta.

Protons shoot on a

collision course, providing

a fireworks show

for those who know how

to interpret the soundless

echoes of strange quarks.

Thursday, March 19, 2009

Student Work

The poetry students have been asked this semester to write poems according to some limitation(s) of their own choosing. So, for example, Melissa Gutierrez has been writing nothing but sestinas. More than one student has been working within syllabic restrictions, as is the case with Erin Arendse. Her poem, below, takes its formal cues from Marianne Moore, but part of the fun of this poem is in how it reveals something about Moore's voice: that it was not just a product of her idiosyncratic commitments to line length or syllabic count. If that were the case, Erin's poem would carry the same aura as Moore's. It doesn't. It carries its own, almost O'Hara-like vibe, while working within the kind of line and stanza limitations we don't see in O'Hara.

Replication with Projector on Vinyl

Searching each cornered tea house and street front

coffee shop hoping the next one will have

a public restroom

obliged to order

every time

“12 oz. house brew please, black.” Each little place

unique yet somehow the same. With Billie

Holiday crooning

in the background at

this one followed

by John Mayer then Norah Jones at the

next. The one on 3rd and State Street has a

wall full of books, 4th

and State’s place features

local working

artisans and a painting of a man

with a coffee mug, staring at walls of

books just like the one

on 3rd street. On 6th

Street, something new:

heat lamp on the veranda, tables for

two and four set in patterns according

to the rule of odds.

Gilpin didn’t know,

neither did Marx,

what he was talking about. You see, I

figured it out. All men are born evil.

If they weren’t, every

tea house would have a

public restroom.

But my grandparents always call at the

worst times and I can’t seem to remember

what I never meant

to forget, so I’ll

answer this one.

“Hello. Yes, I’m fine. How are you?”

~

More poems to come.

Replication with Projector on Vinyl

Searching each cornered tea house and street front

coffee shop hoping the next one will have

a public restroom

obliged to order

every time

“12 oz. house brew please, black.” Each little place

unique yet somehow the same. With Billie

Holiday crooning

in the background at

this one followed

by John Mayer then Norah Jones at the

next. The one on 3rd and State Street has a

wall full of books, 4th

and State’s place features

local working

artisans and a painting of a man

with a coffee mug, staring at walls of

books just like the one

on 3rd street. On 6th

Street, something new:

heat lamp on the veranda, tables for

two and four set in patterns according

to the rule of odds.

Gilpin didn’t know,

neither did Marx,

what he was talking about. You see, I

figured it out. All men are born evil.

If they weren’t, every

tea house would have a

public restroom.

But my grandparents always call at the

worst times and I can’t seem to remember

what I never meant

to forget, so I’ll

answer this one.

“Hello. Yes, I’m fine. How are you?”

~

More poems to come.

Wednesday, March 11, 2009

Hillman on Beauty

Julian Francolino (class participant), meat, oil on canvas

Kevin Scholl (class participant), Exquisite, mosaic from shredded fashion magazines

In James Hillman's essay, The Practice of Beauty, he considers "Suppose we were to imagine that beauty is permanently given, inherent to the world in its data, there on display always, a display that evokes an aesthetic response. This inherent radiance lights up more translucently, more intensively within certain events, particularly those events that aim to seize it and reveal it, such as artworks." "The artist, of course, does indeed reveal the extraordinary in the ordinary. That is the job - not to distinguish and separate the ordinary and the extraordinary, but to view the ordinary with the extraordinary eye of divine enhancement."

Monday, March 9, 2009

L'Engle, Privilege, and Work

We read Madeline L'Engle last week, from her book Walking on Water, and I noted this passage in our discussion:

This week we'll read Auden, who writes the following about the poet:

Free-lance philosopher (really? wow!) Jonathan Ree, on the other hand, suggests there's an ethical upshot to contemplating beauty (which isn't to say all art is conventionally beautiful):

When spring-fed Dog Pond warms up enough for swimming, which usually isn't until June, I often go there in the late afternoon. Sometimes I will sit on a sun-warmed rock to dry, and think of Peter walking across the water to meet Jesus. As long as he didn't remember that we human beings have forgotten how to walk on water, he was able to do it.I said I was troubled by this passage, because it suggests to me an unawareness on L'Engle's part that her ability to contemplate beauty and faith--in this particular context--derives from her privilege. She has access--by ownership, by friendship, by leisure--to enjoy the beauty of "spring-fed Dog Pond," which raises the question: Is art for the privileged, for the people who have time and means to contemplate it? Is my own participation in art merely a product of being born into an upper-middle-class family, with parents who could finance my higher education while I dabbled in this and that?

This week we'll read Auden, who writes the following about the poet:

The condition of mankind is, and always has been, so miserable and depraved that, if anyone were to say to the poet: "For God's sake stop singing and do something useful like putting on the kettle or fetching bandages," what just reason could he give for refusing? But nobody says this. The self-appointed unqualified nurse says: "You are to sing the patient a song which will make him believe that I, and I alone, can cure him. If you can't or won't, I shall confiscate your passport and send you to the mines." And the poor patient in his delirium cries: "Please sing me a song which will give me sweet dreams instead of nightmares. If you succeed, I will give you a penthouse in New York or a ranch in Arizona."(Which suggests I'm either failing spectacularly as a writer or I'm singing to the wrong people.)

Free-lance philosopher (really? wow!) Jonathan Ree, on the other hand, suggests there's an ethical upshot to contemplating beauty (which isn't to say all art is conventionally beautiful):

Beauty is not only a source of pleasure but also an ethical summons, requiring us to “renounce our narcissism and look with reverence on the world,” and offering intimations of the sacred even to those who have no truck with religious belief.Could it be that the young men in this heartening story, college-educated both of them, and like me, children of privilege, were influenced by beauty, or a contemplation of art? Did their classes in literature or art history--or whatever they took in the humanities--have any influence in their bold plan for revitalizing their hometown, when they could have chosen more personally lucrative paths? Are they, in fact, in the process of renouncing their narcissism? I don't know. But, as L'Engle might say, their actions, seen from the right angle, could be understood as two men remembering how to walk on water.

Friday, March 6, 2009

Poetry of Making Lists

We talked in class briefly about what I heard the poet Dean Young call "the intrinsic poetry of lists." Marianne Moore often traffics in lists. "The Steeple-Jack," for example, takes a detour from the describing the sea-side town just to revel in list-making, and as we read Frank O'Hara's work in the coming weeks, you'll see the pleasure he takes in listing the activities of an afternoon, especially in what he calls his "I-do-this-I-do-that" poems. Then there's this song, a favorite of my kids, which I had mentioned in class:

It's the excess of lists that often charms. They go on longer than we might expect, and somehow, when they threaten to bore, they can re-enchant us by their momentum and conviction, like a fan whose praise of a singer or movie passes through obsession and into the sublime. (I hope I'm not overstating things...) I've been reading George Herbert's The Temple lately, and the following poem, a list poem, has been something I find myself returning to in the past few weeks for nourishment. Each quality he mentions suggests to him another quality, and another. And another.

That ending! Read the poem again and OUT LOUD.

It's the excess of lists that often charms. They go on longer than we might expect, and somehow, when they threaten to bore, they can re-enchant us by their momentum and conviction, like a fan whose praise of a singer or movie passes through obsession and into the sublime. (I hope I'm not overstating things...) I've been reading George Herbert's The Temple lately, and the following poem, a list poem, has been something I find myself returning to in the past few weeks for nourishment. Each quality he mentions suggests to him another quality, and another. And another.

Prayer (I)

Prayer the Churches banquet, Angels age,

Gods breath in man returning to his birth,

The soul in paraphrase, heart in pilgrimage,

The Christian plummet sounding heav'n and earth;

Engine against th' Almightie, sinners towre,

Reversed thunder, Christ-side-piercing spear,

The six-daies world-transposing in an houre,

A kinde of tune, which all things heare and fear;

Softnesse, and peace, and joy, and love, and blisse,

Exalted Manna, gladnesse of the best,

Heaven in ordinarie, man well drest,

The milkie way, the bird of Paradise,

Church-bels beyond the starres heard, the souls bloude,

The land of spices; something understood.

That ending! Read the poem again and OUT LOUD.

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

The Worth of the Work

A nice example of the kind of work Sayers champions can be examined in this article. My favorite line:

These Brooklynites, most in their 20s and 30s, are hand-making pickles, cheeses and chocolates the way others form bands and artists’ collectives.

It takes work to make this kind of thing happen. And patience. And interest in the thing itself. I'm reminded of Sayers' description of the shareholders of the brewery who don't just want to know about the bottom line but who "want to know what goes into the beer." Such principles of work and patience apply to visual artists and writers, of course, but artists and writers always want to make a mark, to achieve for their work some permanence. What about those who, like these Brooklynites, make something one consumes (in the truest sense) and which, by that consumption, vanishes from the world? There's something lovely in the idea, because it means finding validation in things other than in what is tangible and measurable: community, sustainability, stewardship, the pleasure of process, the worth of the hand-made thing. A show like How It's Made finds its audience in showing us the way what's lying around the house is manufactured. As one writer has pointed out (in an article I can't find), part of the show's mesmerizing appeal is its lack of a human presence. Our stuff - including much of our food - is made mostly by robots on assembly lines. I don't want to paint too broad and unfair a picture, but you don't hear a robot remark about the Fritos it has roasted and bagged, "These are pleasant to the sight and good for food..." Which may be a long way of explaining the appeal Richard Scarry's books have for my children (and me!).

Monday, February 23, 2009

Presentations

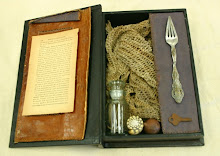

Our first group poet/arist presentations looked at the work of Joseph Cornell and Marianne Moore. The presentations focused on the voice and vision of Moore and Cornell's practice.

Confusion of Categories

One of the things Dorothy Sayers' writes in her essay "Why Work?", written during WWII in a period of scarcity and rationing, a crisis not totally unlike the economic crisis we currently face:

We have had to learn the bitter lesson that in all the world there are only two sources of real wealth: the fruit of the earth and the labor of men; and to estimate work not by the money it brings to the producer, but by the worth of the thing that is made.The best way to understand "the thing that is made," according to Sayers, is to "serve it." She writes,

[The worker's] satisfaction comes, in the god-like manner, from looking upon what he has made and finding it very good. He is no longer bargaining with his work, but serving it. It is only when work has to be looked on as a means to gain that it becomes hateful; for then, instead of a friend, it becomes an enemy from whom tolls and contributions have to be extracted. What most of us demand from society is that we should always get out of it a little more than the value of the labor we give to it. By this process, we persuade ourselves that society is always in our debt - a coviction that not only piles up actual financial burdens, but leaves us with a grudge against society.Further, Sayers writes,

The greatest insult which a commercial age has offered to the worker has been to rob him of all interest in the end product of the work and to force him to dedicate his life to making badly things which were not worth making.Finally, describing how the damage a confusion of categories wreaks on society - in this case, a confusion of the right role of work in a person's life - is not mitigated by good - or even "holy" - intentions, Sayers comments,

No piety in the worker will compensate for work that is not true to itself; for any work that is untrue to its own technique is a living lie. [Emphasis mine.]This applies to the artist's and writer's work, but also to the furniture maker's, the gardener's, the grocer's, the engineer's and the rest. But it seems especially relevant to this class, where we flirt with the idea of blurring categories. We tread carefully, therefore. A short and entertaining essay, entitled "Great Book, Bad Movie," which explores what happens when you don't tread carefully, can be read here.

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Miscellany

A lot has happened in the past week that has gone undocumented here. Our discussion of Dorothy Sayers' essay "Why Work?" has stayed with me, as has the idea, described a couple posts down, that progress brings tradeoffs. Two columns that address this, one of which is about the movie Wall-E, can be found here and here.

Sayers' essay also prompted my searching of Genesis, some passages of which I shared in class:

More:

Finally:

Sayers' essay also prompted my searching of Genesis, some passages of which I shared in class:

And God saw that is was good. - 1:12bThis is the first time this phrase is used in the creation story. One of the OED entries defines 'good' as "Having in adequate degree those properties which a thing of the kind ought to have," a definition anyone who makes should understand.

More:

And the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed. Out of the ground the LORD God made to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food... - 2:8-9Here, aesthetic consideration ("pleasant to the sight") is fused with utility ("good for food").

Finally:

The LORD God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it. - 2:15Before the fall, the man was put to work. He was made to work. Describing Adam & Eve's Edenic labor, Milton has it thusly:

On to their morning's rural work they hasteAnd, last, at the risk of making this post 'overwoody,' a word about 'moral,' as used in Eagleton's definition of poetry, which we discussed yesterday:

Among sweet dews and flow'rs; where any row

Of fruit-trees overwoody reached too far

Their pampered boughs, and needed hands to check

Fruitless embraces... v: 211-15

A poem is a fictional, verbally inventive moral statement in which it is the author, rather than the printer or word processor, who decides where the lines should end. 25The OED, again, on "moral" (first definition):

Of or relating to human character or behaviour considered as good or bad; of or relating to the distinction between right and wrong, or good and evil, in relation to the actions, desires, or character of responsible human beings; ethical.This seems to comport with Eagleton's elucidation of the term:

...morality in its traditional sense...is the study of how to live most fully and enjoyably; and the word 'moral' in the present context refers to a qualitative or evaluative view of human conduct and experience. 28This means that poems that don't appear to have a readily discernible moral dimension do, in fact, even poems as (merely) observational as haiku, like this one by Matsuo Bashō:

By the old temple,

peach blossoms,

a man hulling rice.

Friday, February 13, 2009

Ways of Seeing

Francis Alys:Fabiola

Francis Alys:FabiolaOne of the required class texts is John Berger's, Ways of Seeing. In discussing the first chapter we spent a good deal of time talking about issues of reproduction, originality and place. A work of art, the physical object, is created with the intention of physicality. The surface of the work is imprinted with the presence of the artist's actions. It's generally assumed that this surface will be received (seen) by an individual viewer in a specific location offering what Daniel Siedell refers to as "a unique and complex "hypostatic union" between sensuous material and rational ideas." While reproduction and the technology of distribution provide a democracy of accessibility one does have to seriously consider what is lost in the vision and voice of the work when it is delivered/received via web or powerpoint.

A few days after the class discussion I stumbled into an amazing exhibition at LACMA. Francis Alys: Fabiola, a collection of nearly three hundred objects, all original works, all copies of a single work. The subject matter is a fourth century Christian saint known as Fabiola. The prototype from which every work derives is a lost painting by a late-nineteenth century French academician named Jean-Jacques Henner. Original, reproduction, original.

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Learning and Losing

The discussion about Dorothy Sayers' remarkable "Why Work?" today was fantastic, but I fear her essay can make us (or me) feel despair, given how far things have progressed away, in the last sixty or so years, from her vision of work and society. This afternoon, I was reminded of the following passage from Eagleton, Chapter 1, which speaks to the concerns we have about technological progress and its consequences:

If modern technology can be oppressive, it can also be emancipatory. If it can dilute experiences, it can also increase their accessibility. Even the Giant's Causeway Experience can help to educate us, in however formulaic a fashion. History-as-heritage is arguably preferable to no history at all. Such cultural technology opens up a world of possibility unimaginable to our ancestors. Only a dialectical viewpoint, one which weighs the gains of modernity along with its losses, can do justice to it. And this is inimical alike to the cultural Jeremiahs, for whom civilisation has been going downhill ever since the invention of the wheel, and the wide-eyed cultural progressivists, for whom R.E.M. has thankfully put paid to Rembrandt.Can such a (more hopeful) view of modern life fit with Sayers' argument? [UPDATE: In the current issue of the New Yorker, an article about Florida reads as a demonstration of the kind of judgment Sayers describes. A companion video to the article can be viewed here.]

Avant-garde artists like the Futurists and Surrealists plucked new kinds of art from the very speed, flatness, flux, randomness, irregularity, fragmentation and multiplicity of modern experience. A whole new poetics seemed possible. The most celebrated poem of the twentieth centure, T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land, registers this haemorrhaging of experience from modern urban life, but views it as a spiritual catastrophe. Poets like Mayakovsky, Brecht and Breton, by contrast, did not look upon the emptying of the human subject with horror. Maybe being scooped out and dismantled might prove a prelude to being put together again, this time more productively. To learn something, as George Bernard Shaw remarked, always feels at first like losing something. 20-21.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Second Post

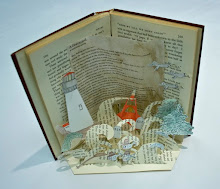

Our first class field trip involved visiting two museums. The first was the Hammer Museum to see "Oranges and Sardines, conversation on Abstract Painting". The title is in reference to Frank O'Hara's "Why I am not a Painter". The second exhibition we visited was at MOCA Pacific Design Center. "To Illustrate and Multiply: an Open Book" This was an extensive survey show of artist books.

View the Marianne Moore slideshow by clicking here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)